- Email Norman

- P.O. Box 38, Millwood, VA 22646

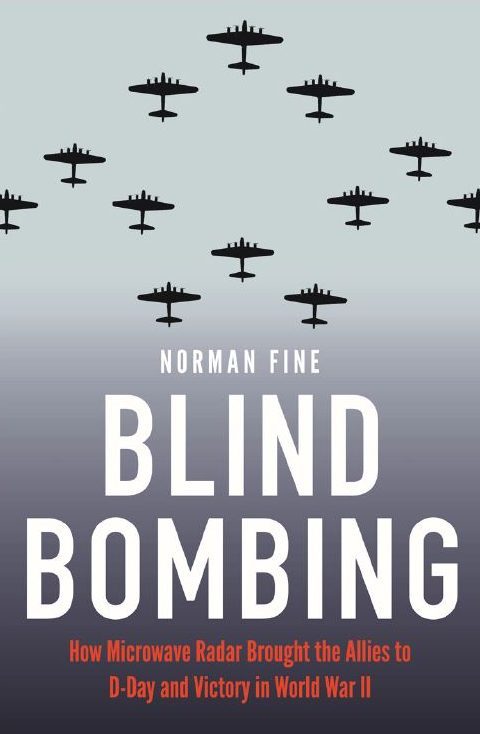

About Blind Bombing

Award Winning Historical Non-Fiction

Readers of World War II history know that the heavy bombers of the U.S. Eighth Air Force, based in England, along with those of Britain’s Royal Air Force set the stage for D-Day on June 6, 1944, by neutralizing Nazi Germany’s war-making infrastructure: production plants, energy sources, and transportation hubs. That was the mission and purpose of the Allied Strategic Bombing Campaign. General Eisenhower was not about to put 150,000 men on the Normandy beaches with the German Airforce, the Luftwaffe, still a potent threat.

The Untold Story

What the history books never told us, however, was that by the end of 1943, with only five months to go until D-Day, the bombing campaign had failed in that mission. Why? Because of the dreadful European weather. Winter, late fall, and early spring were often stormy and mostly overcast. Since the start of the U.S. bombing campaign in 1942, statistics revealed that seventy to eighty percent of all planned bombing missions were scrubbed or recalled. The Eighth Air Force was able to complete only seven missions a month on average. Not enough. The thick weather was affording German industry and transportation hubs enough time to repair bomb damage and keep running.

With D-Day just five months away, Air Force leaders knew they had to do something different. They had to complete more missions, despite the weather. But how? Even with their Norden bombsights, which were optical instruments, if they couldn’t see the targets through the overcast, they couldn’t bomb them.

With Few Options, A Major Change

Air Force leaders reluctantly listened to two far-seeing Eighth Air Force officers, Col. Cowart and Major Rabo, who had been cooperating with the civilian scientists at MIT’s Radiation Lab in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Despite strong Air Force opposition, the officers persuaded their leaders to try a new tactic. Throughout December of 1943, a test fleet of twenty B-17s, each fitted with a new top-secret H2X (‘Mickey’) radar, hurriedly hand-built by MIT technicians, was put into service at a heavy bomber base in Alconbury, England. Even under totally overcast conditions, a Mickey-equipped bomber would lead the formations, navigate to the target, “see” the target through the overcast, and drop the first bombs and marker flares for all the planes following to see where to drop their own bombs. Blind Bombing!

A month later, in January 1944, the Eighth Air Force bombing protocols were officially overhauled. With fewer than twenty radar-equipped heavy bombers in Europe to lead the thousands of bombers already in combat, every bomber wing on every bombing mission would be led by a radar-equipped Mickey plane, no matter the weather.

Just five months later, on June 6, 1944, the day that Eisenhower sent 150,000 armed men to the Normandy beaches, there was scarcely a German plane in the sky to oppose them. Of the German planes still airworthy, there were no spare parts to repair them, no fuel to run them, and few experienced pilots to fly them. They’d been shot down trying to defend against the relentless assault made possible by microwave radar, a technology possessed solely by the Allies and unknown to the enemy.

The Key to Microwave Radar

All the WWII warring nations had radar, but there was the primitive radar of the times, and there was microwave radar. Only the Allies had microwave radar, and the difference in performance between the two was akin to that between the musket and the rifle. And the Allies had yet another advantage. Other than Great Britain, Canada, and the United States, no other nation in the developed world knew that microwave radar was even possible to achieve.

This advanced radar was made possible by the invention of a top-secret gadget on the very eve of the war, November 1939, by two British physicists at the University of Birmingham. The inventors, John Randall and Harry Boot, called their new invention a cavity magnetron. Physically, it was small, able to be held in the palm of a man’s hand. Unknown to the enemy, the cavity magnetron improved the performance of the primitive radar known to the rest of the developed nations by almost a thousand-fold! And only the Allies had it.

First, Save Britain

Even before the rescue of D-Day’, new Anti-Surface Vessel (ASV) radars designed around the cavity magnetron had already conquered the German U-boats that were wreaking havoc in the Atlantic. There were months in 1942 when U-boats sank more shipping tonnage bound for English ports than the Allies could replace. And without the loss of a single U-boat! Admiral Doenitz, Commander of the German U-boat fleet, wanted more U-boats and boasted he could win the war with the U-boats alone.

Newly designed ASV radars, installed in British coastal patrol planes, long-range American B-24 bombers, and destroyer escorts of both navies pushed the U-boats from the shipping lanes and won the Battle of the Atlantic. England, an island nation, needed open shipping lanes for its very survival. By mid-1943, with Doenitz puzzling over how his U-boats were being detected, his dream had vanished.

The cavity magnetron overcame the two most serious obstacles to D-Day: the U-boats and the thick European weather. It was surely the single new invention most influential in winning the war in Europe.

Scientists, Warriors, and A Family Connection

Radars designed around the cavity magnetron were used during the war in both the European and the Pacific theaters by every branch of the Allied military for a variety of purposes. During the course of the war, the Raytheon Company alone produced more than a million cavity magnetrons. Despite all the important tactical uses found for microwave radar, two were more than serious. U-boats threatened Britain’s very existence and the perpetually overcast European weather kept the Eighth Air Force heavy bombers on the ground. These were major obstacles to D-Day and victory in Europe, and they dominate the scope of Blind Bombing.

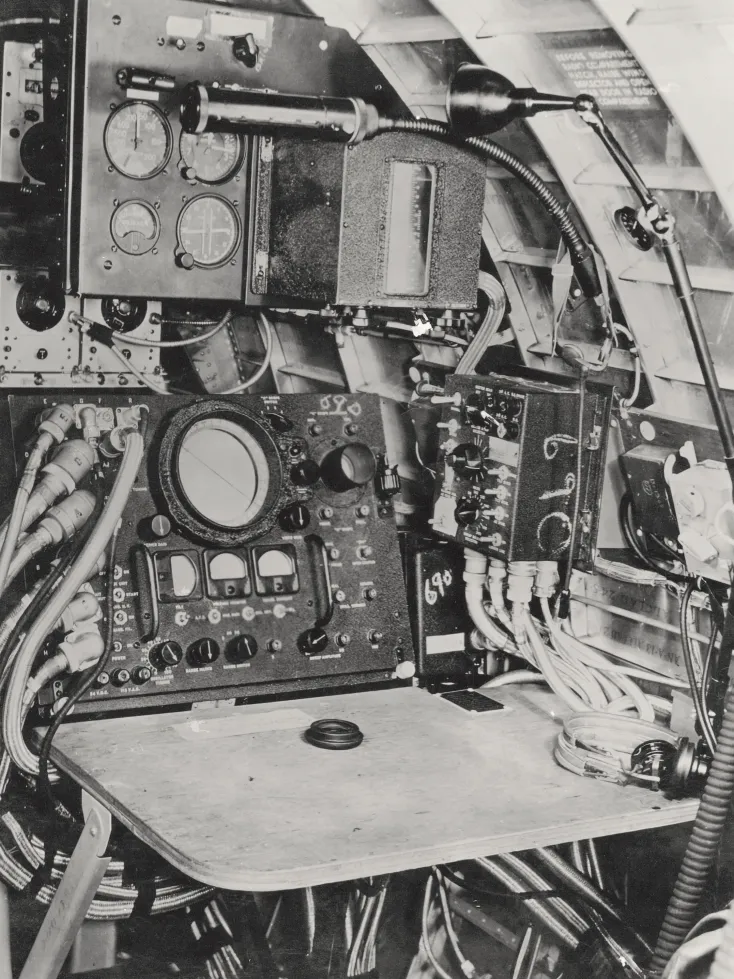

Twenty years ago, author Fine spoke at length to two men who played critical roles in the radar war. One was the brilliant, cocky, and somewhat paranoid scientist at the Radiation Lab at MIT, George Valley, who was project leader for the H2X blind bombing radar design program. The other was the young Air Force B-17 navigator, Lt. Stanley Fine. Uncle Stan was caught up in the peacetime draft in 1941 at the age of twenty-one. Three years later, as a trained B-17 navigator, he was secretly trained with nine others on the operation of George Valley’s blind bombing radar, the H2X, and then chosen to bring the first production model of the H2X ‘Mickey’ radar off the Philco Corporation’s production line to England to begin his combat tour. These men bring a personal dimension to the story through their own words.

The development and implementation of microwave radar in World War II is a story of unlikely partners who were able to escape the confines of their disparate and close-knit constituencies, reach out across cultural chasms to others for help, strive for achievements well beyond the limits of known parameters, and all the while resist the pessimists, naysayers, and established prejudices. They were politicians and scientists, army generals and university presidents, philanthropists and businessmen, earthy war veterans and innocent young physicists, Brits and Yanks. Meet these personalities who gave so much to maintain democracy’s dream in the pages of Blind Bombing.

How MIT’s Rad Lab rescued D-Day

After two British physicists invented a revolutionary gadget, MIT researchers used it to develop the radar devices that helped defeat the Nazis. An H2X radar ...

Read More