After two British physicists invented a revolutionary gadget, MIT researchers used it to develop the radar devices that helped defeat the Nazis.

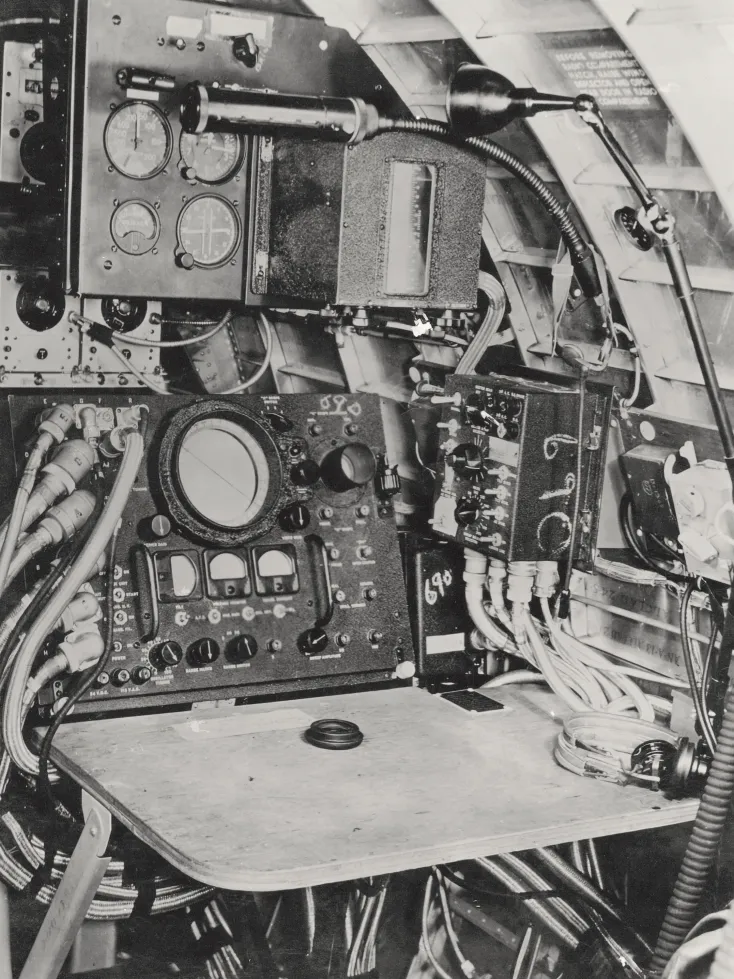

An H2X radar station installed above the starboard wing in a B-17. Courtesy of the Author.

On June 6, 1944, the Allies deposited nearly 160,000 troops on the beaches of Normandy, France, in what still stands as the largest land invasion by sea in world history. D-Day would, of course, prove to be a critical milestone leading to the Allied victory in World War II.

But were it not for the invention of a new gadget in November 1939, D-Day might never have happened. Had it been attempted without said gadget—a high-frequency radio transmitter known as the resonant cavity magnetron—it might well have failed.

This is the story of how the MIT Rad Lab—formally named the MIT Radiation Laboratory to confuse the Nazis—was charged with using that top-secret British invention to design, build, and field-test advanced radar equipment that would pave the way for the invasion that helped win the war.